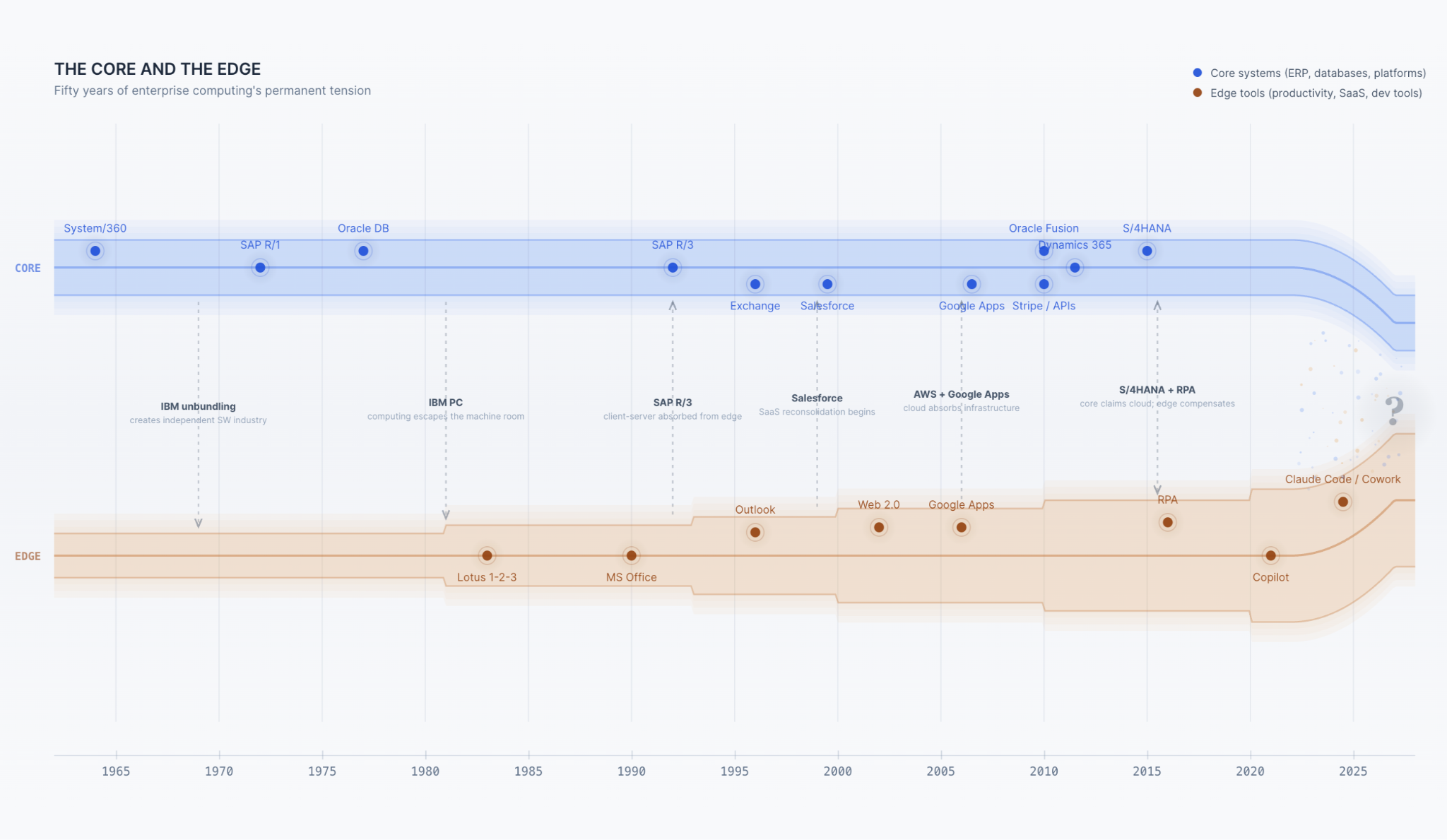

Every decade, enterprise computing promises consolidation. Every decade, work escapes to the edges. Understanding why — and why now could be different — requires tracing two parallel histories that have been running since the 1960s:

… the history of the core (the centralized systems that run the business) … and the history of the edge (the tools people actually use to get work done)

In the beginning, there was no distinction. The core was the edge.

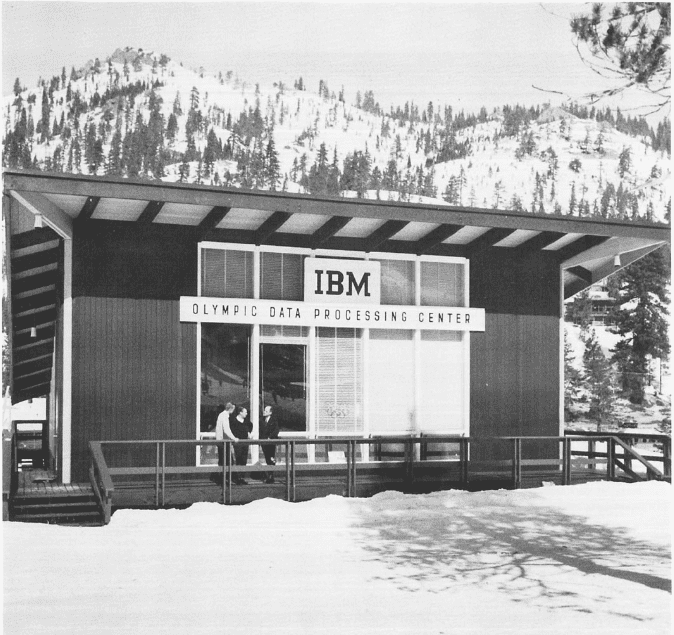

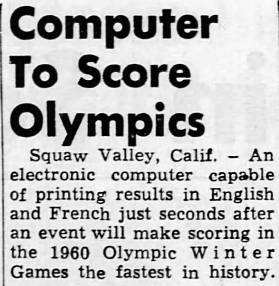

At the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley — a gondola ride away from my home in Alpine Meadows — IBM installed a RAMAC 305 data processing machine in a glass-walled building they called the Olympic Data Processing Center. The RAMAC 305 was the first commercial computer to use a random-access disk drive. RAMAC: "Random Access Method of Accounting and Control."

IBM personnel spent six months doing "discovery," studying the scoring procedures for every winter sport. Subsequently, they developed the programs and built the machine — on site, on a mountain.

Prior to that Games, all event scoring had been calculated by hand on adding machines; athletes and spectators sometimes waited five hours for official results. You may ask, "how hard is it to tally scores for winter sports?"

Harder than you'd think. Consider figure skating alone. According to Olympedia, skaters competed in two segments, compulsory figures and a free skating program, weighted 60/40 in the final score. Each segment was evaluated independently by a panel of judges, each assigning their own rankings, with overall placement determined by a majority placement system that reconciled the judges' independent assessments into a single result. Multiply that across 19 male and 26 female competitors, each performing multiple programs, and you have something that - if you squint - is vaguely reminiscent of what a controller does at month-end: multi-dimensional reconciliation across independent inputs, weighted aggregation under complex rules, and a final result that has to be defensible to everyone watching.

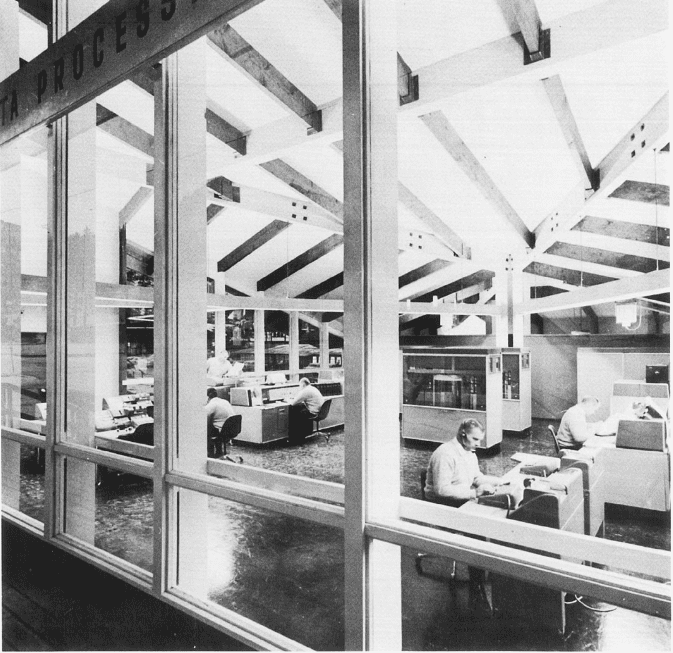

The RAMAC delivered standings in seconds across all 27 events. Its disk held 200-word biographies and performance histories for every competitor, queryable on demand, with results printed automatically in either French or English. Thirty-six IBM staffers and twenty six volunteers operated it. The machine, housed in glass so the public could watch it work, drew as many spectators as the events themselves.

Companies looking to put their accounting and controls through data processing machines in 1960 could expect a similar level of investment: construction and programming of a machine purpose built — quite literally from the ground up — for the specificities and vicissitudes of their exact business.

This image — a computer behind glass, doing work that had previously been done by hand, crowds gathering to watch — is the entire history of enterprise computing in embryo.

The core, on the edge, on a mountain. The machine was the process. The process was the machine. There was no gap between the system and the work, because the system was the work, and everyone could see it happening. Data model, process logic, reporting, even localization (Allô!) — all fused into a single edifice, operated by people who understood both the technology and the domain.

Everything that followed has been an attempt to recover that unity — and a series of increasingly sophisticated failures to do so.

I. The Mainframe Monopoly (1964–1980)

The core: The story inflects with IBM's System/360, announced in 1964 — plausibly the most consequential product launch in the history of business technology. It was a $5 billion dollar, "bet the business" gamble.

Before the 360, computers were bespoke. Each model had its own instruction set, its own peripherals, its own software. Upgrading meant rewriting everything. The 360 introduced a single architecture spanning an entire product line, from small installations to the largest data centers. For the first time, software was portable across machines.

This was the original core. Centralized, capital-intensive, and controlled entirely by proto-IT departments (in this era still called "data processing"). The machine room was the business system. Payroll, general ledger, inventory, order entry — everything ran in a batch on the mainframe, scheduled overnight, with results delivered on greenbar paper the next morning.

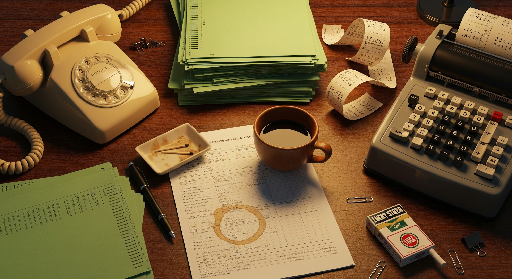

The edge: There was no edge yet. Or rather: the edge was paper. Clerks transcribed transactions onto forms. Data entry operators keyed them in. Reports came back. Decisions were made by managers reading printouts and writing memos. The gap between what the system knew and what people needed was bridged by filing cabinets, adding machines, and institutional memory.

Two things about this era matter for what follows. First, the software was custom. Every company wrote its own. There was no packaged application market to speak of. Second, the data was structured from birth — keypunched into predefined formats, validated on entry. The core was rigid, but it was coherent. Everything in the system had been deliberately put there.

IBM's dominance was so total that it drew antitrust action. The 1969 unbundling consent decree forced IBM to price software separately from hardware, inadvertently creating the independent software industry. Without that legal accident, neither Oracle nor SAP would exist in their current form.

II. The Minicomputer Crack (1970–1985)

The first fissure in the mainframe monopoly came not from below but from the side. Digital Equipment Corporation's PDP and VAX lines, Hewlett-Packard's 3000 series, and later IBM's own AS/400 put computing power into departments that couldn't justify — or couldn't get time on — the corporate mainframe.

This had a profoundly decentralizing effect. Engineering groups bought their own machines. Regional offices ran their own systems. The minicomputer didn't replace the mainframe; it grew up around it, serving workloads the central IT organization either couldn't prioritize or couldn't deliver fast enough.

Two companies founded in this period would reshape everything. Oracle (1977) built a relational database — commercializing Edgar Codd's theoretical work at IBM, which IBM itself was slow to productize. SAP (1972) built something arguably more radical: the first integrated enterprise application, called RF, for Real-Time Financials, launched in 1973. Running on IBM mainframes, with development and testing taking place on customers' machines – at night and on weekends when otherwise idle. RF was the cornerstone for a modular system that would be known as R/1. Purchasing and materials management (RM) would soon follow. Together, they constituted a breakthrough: software that could integrate all of a company's applications and store data centrally. Amounts would flow from materials management to financial accounting, allowing invoices to be verified and posted in a single step. No more reconciling between separate programs. SAP's insight was architectural: the problem wasn't computing power but integration. They unified a data model, metadata layer, extensibility model (the first "user exit" came in R/3 during order processing flows), authorization model, process engine (tcodes!), and reporting. Tightly coupled, but the seeds were there.

Oracle gave enterprises a general-purpose data platform. SAP gave them a general-purpose business platform. Both were bets on the core. Both would prove generationally correct.

III. The PC Revolution and the Birth of Shadow IT (1981–1995)

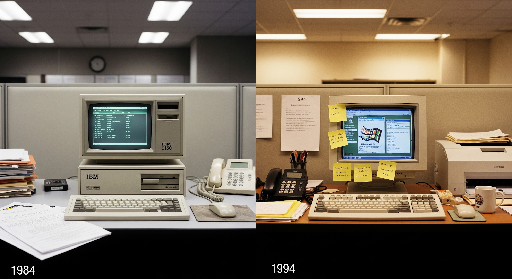

The IBM PC, launched in 1981, was designed to be unimportant. IBM's Entry Systems Division built it in Boca Raton, Florida, far from the mainframe priesthood, using off-the-shelf components.

The Edge Takes Center Stage And an operating system licensed (not purchased) from a small company in Seattle. The decision to use an open architecture and a third-party OS was expedient, if also the most consequential strategic error in business history.

Within five years, Compaq, Dell, and dozens of others were manufacturing IBM-compatible PCs. Microsoft, supplying DOS and then Windows to all of them, captured the value that IBM had given away. By the early 1990s, the PC industry was enormous, and IBM was in crisis — posting an $8.1 billion loss in 1993, the largest in American corporate history at that time.

But the real story isn't about hardware margins. It's about what happened inside companies.

The PC put a general-purpose computer on every desk. And the first thing people did with it was compensate for the shortcomings of the core.

Lotus 1-2-3, released in 1983, is the ur-example. The spreadsheet was not designed to be an enterprise application. It was designed to be an ad-hoc calculation tool, a replacement for the paper worksheets where the calculations that hadn't been programmed yet happened. But it became the de facto platform for every business process the mainframe couldn't or wouldn't accommodate. Budgeting. Forecasting. What-if analysis. Variance reporting. Commission calculations. Inventory reconciliation. Financial consolidation. All of it migrated to spreadsheets — not because spreadsheets were good at these tasks, but because the alternative was a six-month IT project with a requirements committee and a queue.

This is the birth of what we now call "shadow IT," though the term wouldn't be coined for another two decades. It is also the birth of a pattern that has repeated ever since: the core ossifies around the processes it was built for; the edge absorbs everything that changes faster than the core can adapt.

Microsoft understood this better than anyone. The Office suite — Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and eventually Access — wasn't just a collection of productivity tools. It was an alternative platform for business logic. By the mid-1990s, more business rules lived in Excel macros and Access databases than in any ERP system. They were fundamentally ungovernable, undocumented, and completely, utterly essential.

The Core Responds Meanwhile, the core was getting more ambitious. SAP R/3, released in 1992, moved from mainframes to client-server architecture and became the defining enterprise application of the decade. Its premise was total integration: every business process, from procurement to production to financials, in a single system with a single data model. The implementations were brutal — multi-year, multi-million-dollar projects that frequently failed. Hershey's botched R/3 rollout in 1999 left the company unable to ship candy for Halloween. FoxMeyer Drug blamed its SAP implementation for its bankruptcy.

But the companies that survived implementation achieved something real: a transactional core that actually worked. The general ledger balanced. The supply chain was visible. Orders flowed through a single system. For many large enterprises, the late 1990s and early 2000s were the high-water mark of core system coherence.

The irony is that this very coherence accelerated the growth of the edge. The more rigid and integrated the ERP became, the harder it was to change. And the more expensive and slow changes became, the more work people did in spreadsheets instead.

IV. The Network Era: Client-Server, Intranets, and the Email Explosion (1993–2005)

Sun Microsystems' slogan — "The Network Is the Computer" — was premature in the 1980s and prophetic by the mid-1990s. The combination of TCP/IP networking, the World Wide Web, and increasingly powerful servers created a new architectural layer between the mainframe and the desktop.

Inside enterprises, this manifested as the client-server era. Oracle and Microsoft SQL Server replaced file-based databases. Applications were split between server-side logic and desktop clients. Siebel (CRM), PeopleSoft (HR), and dozens of other vendors built departmental applications that ran on this architecture. Each was a small core unto itself — centralized, structured, governed — but the proliferation of them created a new problem: integration. Data lived in silos. Customer information in Siebel didn't match customer information in SAP. The "single source of truth" that ERP promised was undermined by every new best-of-breed application added to the portfolio.

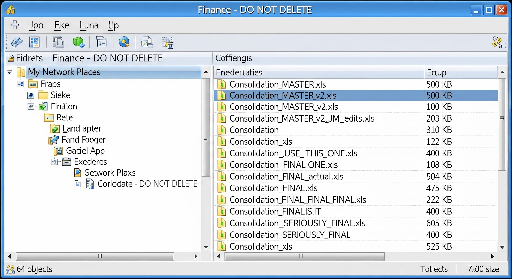

Email and file servers created a parallel universe of unstructured information. Microsoft Exchange (1996) and file shares became the connective tissue of the organization — and another edge platform for business logic. Critical approvals lived in email chains. Financial models lived on shared drives. Version control was a matter of file naming conventions: Q3_forecast_v2_final_FINAL_revised.xlsx.

Lotus Notes, in its heyday, was perhaps the most interesting hybrid. It was simultaneously an email client, a document database, a workflow engine, and an application platform. Companies built thousands of Notes applications — expense approvals, project tracking, compliance workflows — that were too important to discard and too idiosyncratic to migrate. Many are still running.

The edge, by now, was not just spreadsheets on desktops. It was a vast, interconnected ecosystem of email, shared files, departmental databases, and ad hoc applications — all sitting outside the governance perimeter of the core but deeply entangled with core processes.

V. The Web and the First Reconsolidation (2000–2012)

The dot-com era reframed computing around the browser. Netsuite, founded in 1998, and Salesforce, founded in 1999 — both helmed by Oracle vets and backed by Larry Ellison — were the first major enterprise applications built entirely for the web — and the pioneers of SaaS (Software as a Service). Their insight was that CRM and ERP didn't need to run in your data center. They could run in someone else's, accessed through a browser, paid for by subscription.

This was reconsolidation, but of a novel kind. Instead of consolidating into the customer's core, SaaS consolidated into the vendor's cloud. Workday (founded by PeopleSoft's co-founder after Oracle's hostile acquisition) did the same for HR and finance. ServiceNow did it for IT service management. Each carved out a domain and centralized it — not on-premises, but in multi-tenant cloud infrastructure.

Google took a different approach to reconsolidation. Google Apps (later Workspace), launched in 2006, attacked the productivity suite directly. Email, documents, spreadsheets, and file storage, all in the browser, all collaborative by default. The pitch was explicitly about eliminating the edge chaos: no more Exchange servers to maintain, no more file shares to back up, no more emailing spreadsheets back and forth. Everything in the cloud, always the latest version. Meanwhile AWS, launched in 2006, reconsolidated in a different dimension entirely. By offering raw infrastructure as a service, Amazon made it trivially cheap to stand up new systems. This was a gift to software vendors (who no longer needed to ship installable software) and a mixed blessing for enterprises (who now had a new mechanism for proliferation — the cloud account as the new departmental server).

Microsoft, after initially dismissing the threat, responded with Azure (2010). With Office 365 (2011), it rebuilt its entire productivity stack around cloud services — Exchange Online, SharePoint Online, OneDrive, Teams. Business core applications followed in 2016 with the launch of Dynamics 365, which brought their on-prem ERP and CRM applications under one cloud-hosted tent.

Microsoft Revenue by Segment

FY2005–FY2025 · Fiscal years end June 30

Notes

FY2005–FY2015 shown as total revenue (segment reporting in current structure began FY2016).

Azure launched commercially in February 2010. Intelligent Cloud became Microsoft's largest segment in FY2020.

*FY2025 uses revised segment definitions (announced Aug 2024). Windows Commercial components moved from More Personal Computing to Productivity & Business Processes. This inflates P&B and deflates MPC relative to prior years. Intelligent Cloud was also restated — prior-year IC under new definitions was ~$87.4B, meaning actual IC growth was ~22% YoY, not the ~1% the chart visually suggests vs. FY2024's old-definition $105.4B.

FY2025 segment totals: P&B $120.7B · IC $106.3B · MPC $54.8B · Total $281.7B (computed from quarterly earnings releases).

Microsoft Cloud revenue reached $168.9B in FY2025 (+23% YoY). Azure alone surpassed $75B annually for the first time.

The reconsolidation was real: by the late 2010s, the chaotic landscape of on-premises file servers and email infrastructure had been largely absorbed into one of two clouds (Microsoft or Google).

But notice what happened. The infrastructure was reconsolidated. The behavior was not. People still built financial models in Excel. They still tracked projects in spreadsheets. They still ran critical reconciliation workflows by emailing files between team members and manually copying data between systems. The cloud made collaboration easier and IT operations simpler, but it did nothing to address the fundamental gap: the core couldn't accommodate the process, so the process lived at the edge, and moving the edge tools to the cloud just meant the workarounds were now cloud-hosted workarounds.

VI. The Mobile and API Economy (2010–2020)

Apple's iPhone (2007) and iPad (2010) introduced a new class of endpoint: personal, always-connected, and entirely outside IT's control. "Bring Your Own Device" policies were less a choice than a capitulation. Employees were going to use their phones for work regardless of policy; the only question was whether IT would try to manage the situation or pretend it wasn't happening.

The more consequential development was the API economy. As cloud services matured, they exposed programmatic interfaces. Stripe (2010) turned payments into an API call. Twilio did the same for communications. Plaid for banking data. The implications for enterprise architecture were profound: for the first time, core business capabilities could be composed from external services rather than built internally or purchased as monolithic applications.

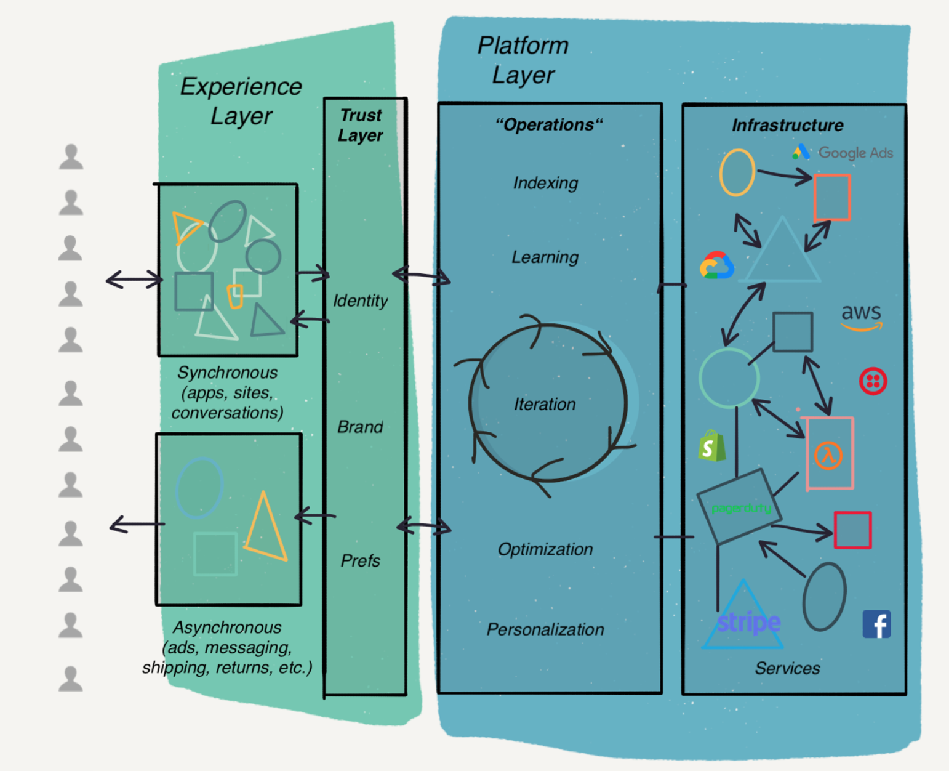

This amounted to a quiet but fundamental rethinking of what a firm even is. Michael Porter's value chain — the dominant model since 1985 — decomposed a company into a linear pipeline of primary and supporting activities. But by the mid-2010s, the most sophisticated technology companies had stopped looking like pipelines at all. They looked more like switchboards. A piece I wrote at Segment in 2020 tried to name what was happening: the emergence of what I called the "Request/Response Model" of the firm. Instead of a sequential chain of activities, the modern enterprise was becoming a hub that orchestrated external capabilities through API calls — sending requests, receiving responses, composing outcomes. Porter's pipeline assumed you owned and operated each link. The request/response firm assumed you owned the orchestration logic and outsourced the rest to best-in-class providers.

The strategic implication was sharp: when a company plugs in Stripe for payments, it's effectively hiring the entire Stripe organization — the Collison brothers, their engineering team, their compliance infrastructure, their bank relationships — to run that function. The same for Twilio and communications, Plaid and banking data, Checkr and background checks. Every API integration was a make-vs-buy decision resolved at the speed of a code commit. Packy McCormick picked up the thread in his widely-read APIs All the Way Down, crystallizing the argument for a broader audience: "It's actually becoming crazy to build your business in any way other than using all APIs except your point of differentiation."

This created a new architectural pattern — the enterprise as a platform of platforms, stitched together by APIs and integration middleware (Segment was acquired by Twilio for 3.5bn. That and MuleSoft, acquired by Salesforce for $6.5 billion in 2018, give some indication of how valuable this plumbing became). The core was no longer a single system but a constellation of services, some on-premises, some SaaS, some custom-built on cloud infrastructure.

What the request/response model rewarded — and what the market richly valued — was asset-lightness. The firm that owned the least and orchestrated the most was considered the most modern. Revenue multiples for pure SaaS companies reflected this: investors prized recurring revenue, low marginal costs, and minimal capital intensity. The companies that had gone "asset-heavy" — those with physical infrastructure, proprietary data, deep domain operations — were out of fashion. Heavy was slow. Light was scalable.

Now what? That consensus held for a decade. It is now unwinding. As AI collapses the cost of producing software toward zero, the market has started to question what, exactly, a pure software company is worth when anyone can spin up a competitive product in weeks.

The companies with durable assets — proprietary data, regulatory moats, physical infrastructure, and - in the realm of pure software, deeply embedded operational workflows — are suddenly back in favor, precisely because those things are hard to replicate with a language model and a weekend. The request/response model of the firm didn't go away, but the market has remembered that the most defensible position in a network of API calls is to be the node that can't be swapped out.

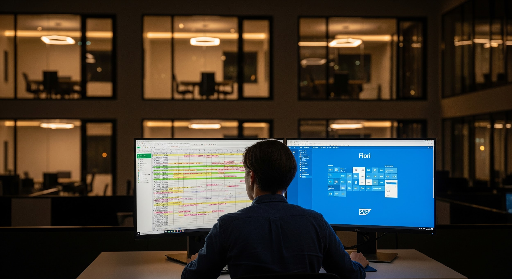

Edge workers. And yet, through all of this architectural sophistication, the spreadsheet remained. McKinsey estimated that finance professionals spent 40% of their time on data gathering and reconciliation. Deloitte surveys consistently found that the majority of financial reporting processes depended on spreadsheets. The core systems were more capable than ever. The integration was better than ever. And people were still manually pulling data from three systems into Excel to figure out whether the numbers were right.

Why? Because the core is optimized for transactions, not for judgment. ERP systems are magnificent at recording what happened. They are poor at helping humans figure out what should happen, whether what happened was correct, or what to do when the data doesn't match expectations. These analytical, investigative, and decision-support tasks — the work of controllers, analysts, and operational managers — have lived at the edge for forty years because the core was never designed for them.

VII. The Cloud ERP Transition and the Persistence of the Edge (2015–2023)

SAP's announcement of S/4HANA (2015) and Oracle's push toward Fusion Cloud represented the most significant core system transitions since the client-server era. Both were bets that the next generation of ERP would be cloud-native, in-memory, and capable of absorbing workloads that had historically escaped to the edge.

The transitions have been enormously expensive and disruptive. SAP's own timeline for sunsetting ECC support has been extended repeatedly — now stretching to 2027 — because customers simply cannot migrate fast enough. Oracle's acquisition strategy (PeopleSoft, Siebel, NetSuite) left it with multiple product lines and complex migration paths. Microsoft's Dynamics 365, rebuilt on Azure, represented a credible mid-market alternative but carried its own integration complexity.

And the edge adapted, as it always does. Robotic Process Automation (RPA) — UiPath, Automation Anywhere, Blue Prism — emerged as a category precisely because the core couldn't change fast enough. RPA was, architecturally, an admission of failure: rather than fixing the system, you built a robot to click through the same screens a human would. The fact that RPA became a multi-billion-dollar market tells you everything about the state of core system adaptability.

Low-code platforms (Appian, Mendix, Microsoft Power Platform) were a more sophisticated response to the same problem. They let business users build applications without waiting for IT — which is to say, they formalized and partially governed the shadow IT that had been running in spreadsheets for decades.

VIII. The AI Disruption: Starting from the Edge (2023–Present)

Large language models arrived in enterprise consciousness with ChatGPT in late 2022 and have been absorbed with extraordinary speed. But look carefully at where the impact has landed.

The first wave is almost entirely at the edge.

… GitHub Copilot and its successors have transformed software development — an edge activity (developers working in their local environments, producing artifacts that eventually merge into shared systems).

… Microsoft 365 Copilot app (formerly Office) embeds AI into Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and Teams — the canonical edge tools

… Google's Gemini integrations do the same for Workspace. Meeting summarizers, email drafters, document generators, code assistants: all of these operate at the endpoint, augmenting individual work.

This makes sense. The edge is where unstructured work lives, and unstructured work is what language models are good at.

The edge is also where the cost of failure is low: a bad email draft or a wrong code suggestion is caught and corrected by the human in the loop. Nobody is letting a language model post journal entries directly to the general ledger.

The coding harness — Cursor, Windsurf, Claude Code, the growing ecosystem of AI-native development environments — feels like the most fully realized version of this pattern. Software development has always been an edge activity with tremendous leverage on the core: developers write the code that becomes the system. Making developers dramatically more productive changes what's possible to build, how fast, and at what cost.

The "harness" breakthrough

But the coding harness also revealed something more general. What made these tools so effective wasn't a breakthrough in prompting or tool design — it was a much simpler insight: give the agent a filesystem and the ability to execute code, and it becomes dramatically more capable than any bespoke tool-calling architecture.

The model doesn't need a custom tool for every task. It needs a unix shell and a directory of files. From those primitives, it can improvise. An Excel agent is just a coding agent pointed at spreadsheet files. A reconciliation agent is a coding agent with access to the data it needs to reconcile and the ability to write Python to do it.

Once this became clear, the next step was obvious: if the most powerful agent harness is bash and a filesystem, and the most consequential unstructured work in the enterprise lives in files on employee endpoints, then the agent should meet the work where it already lives.

Hence Claude Cowork, OpenAI Desktop integrated with Frontier, and the emerging class of endpoint agents with packaged skills for manipulating spreadsheets, drafting and triaging emails, managing documents — the digital equivalent of the office suite, but with an intelligence layer that can actually reason about the work rather than merely store it.

But history suggests a question that every executive should be asking: What happens when this reaches the core?

Every major transition in enterprise computing has followed the same pattern. New capabilities emerge at the edge because the edge is flexible and the core is not. The edge grows. The capabilities mature. And eventually, they are absorbed into — or fundamentally reshape — the core.

Relational databases emerged in research labs and departmental minicomputers before they became the foundation of enterprise applications. Client-server architecture started in departmental systems before SAP rebuilt R/3 on it. The web started as a publication medium before Salesforce and Netsuite turned it into an application platform. AWS empowered startups long before before the largest enterprises migrated their most critical workloads to it.

The current wave of AI has started, predictably, at the edge. The tooling for individual productivity — coding, writing, analysis — is maturing rapidly. But the core enterprise systems, the ones that manage financial transactions and supply chains and regulatory compliance, are the same systems that have resisted every previous generation of disruption until they didn't.

SAP R/3 replaced custom mainframe code. S/4HANA is replacing R/3. Each transition was unimaginable until it was inevitable.

The distance between an AI that helps a developer write code faster and an AI system whose core business processes continuously self-assemble, self-optimize, and largely self-govern — under the guidance of the knowledge workers who drive them and within the control of the principals accountable for their compliance — is narrower than it appears, and closing.

But the history told cleanly — edge leads, core follows — is too neat. The actual motion is less like a march and more like a double pendulum: a heavy arm (the core) swinging in long, slow arcs, and a light arm (the edge) whipping around it, sometimes in sync, sometimes wildly divergent, always tethered. The core never simply absorbs the edge's innovations. It claims them — rebrands them, repackages them — while preserving its own structure, because its structure is what makes it the core. The edge, tethered but not contained, keeps whipping forward.

Watch the seam between the two arms. It's where the interesting failures live.

- IBM absorbed the minicomputer by building the AS/400 — a brilliant machine that became its own stranded ecosystem.

- SAP absorbed client-server by rebuilding R/2 as R/3, but the rigidity of the data model survived the architectural transition intact; the customization problem that makes implementations brutal today was baked in during the 1990s.

- Oracle absorbed SaaS by acquiring PeopleSoft, Siebel, and NetSuite, then spent a decade trying to converge product lines that were architecturally incompatible.

- Salesforce absorbed AI by rebranding its analytics as "Einstein" — same CRM schema, same process architecture, new label. Agentforce, in tandem with Data Cloud, is actually interesting and probably the most fullthroated articulation of what a new core might look like from an incumbent.

- SAP's S/4HANA is "cloud," but the migration timelines, the consultant armies, the configuration hell are structurally identical to 2005; it is a faster version of what customers already had, not a different kind of thing.

- Microsoft bolted Copilot onto Office — and built what Benioff calls "Clippy 2.0." It can summarize your emails, but it isn't rewiring your business processes in Dynamics. You plug agents in to replace or augment the human work. Not to retrofit or constitute the core system itself.

The edge got an AI assistant. The core got a press release.

The pattern at the seam is always the same: the core claims the new capability but cannot metabolize it without changing its own structure, which it cannot do, because rigidity is the price of being the system of record. So the real innovation keeps happening at the edge, connected to the core by increasingly strained integration points — and each generation of edge innovation gets a little closer to the kind of work the core was supposed to own.

That's what makes this moment different from the others, or at least worth watching more carefully.

Previous edge innovations — spreadsheets, email, SaaS, RPA — compensated for the core's limitations without challenging its role.

They were workarounds. Valuable, even essential, but structurally subordinate. The current generation of AI, starting from coding harnesses and endpoint agents, is building something that looks less like a workaround and more like an alternative: systems that can reason about business processes, not just execute predefined ones. Systems that don't need a six-month implementation to accommodate a new workflow, because they can assemble the workflow themselves.

The pendulum is still swinging. It always is. But the light arm is getting heavier — and the question for every enterprise executive is whether the next swing brings the edge and the core into a new equilibrium, or whether the core, finally, learns to do what the edge always has: adapt as fast as the business demands.

Maybe we need a new core. Maybe the core needs a new layer. Follow along as we show you what that might look like.